There are many reasons why we fail to get to where we want to go, especially when we fail to determine what the destination we aim for looks like, because of a strange default in imagination or because we stumble over short deadlines and immediate reality. And to get to a reality that is different from the one we can foresee, the ability to imagine a different destination, an alternative future, is essential. We must, in other words, work back from the future towards the present, imagining a path from “what I want to see around me in seven years” to “what is around me today”. Because the path we choose, especially when it comes to change, is good if it answers this question: Will it lead me to a desirable future?

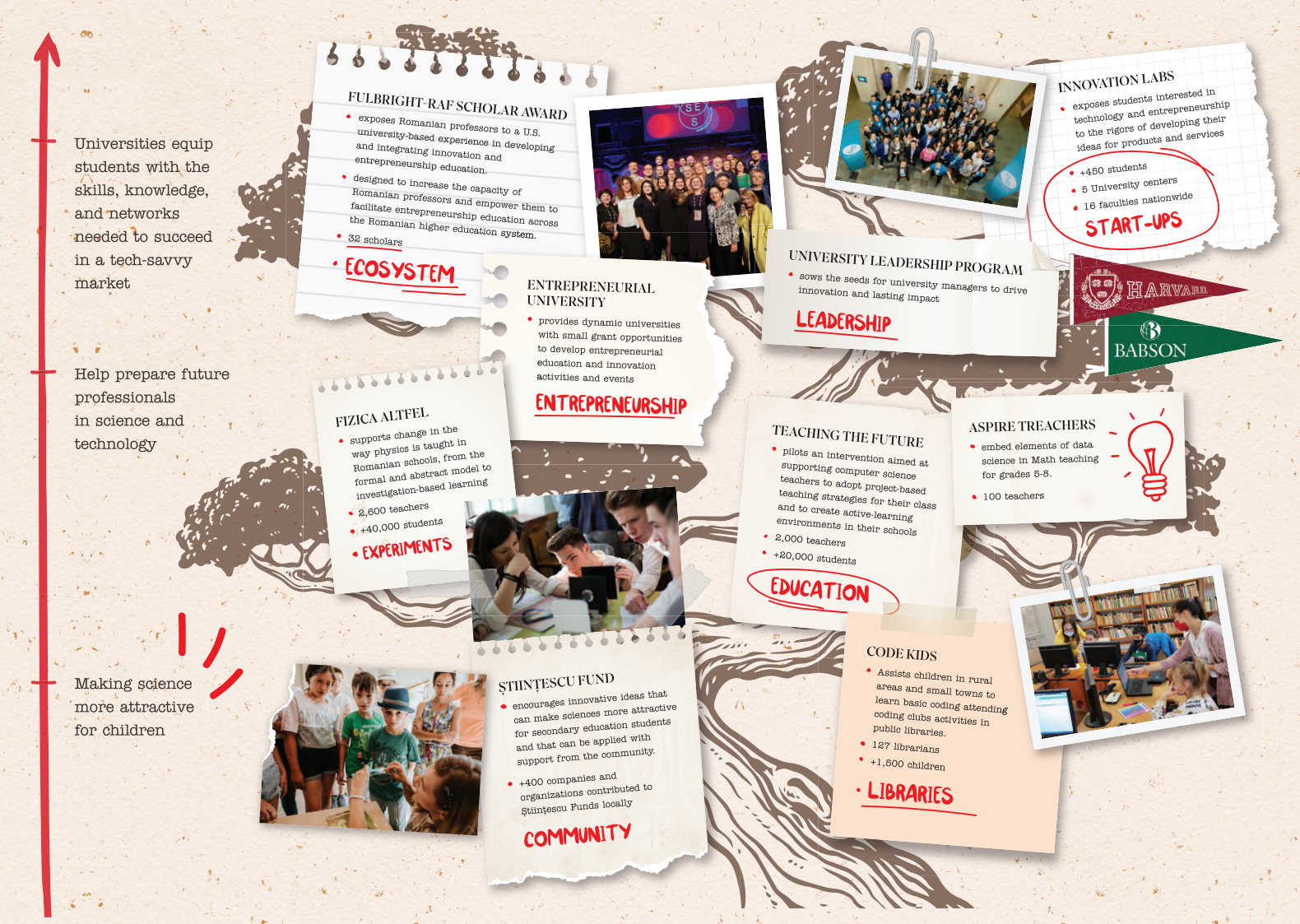

When the Romanian-American Foundation (RAF) started working in technology and innovation, it began by spending months in strategic conversations with dozens of stakeholders: universities, companies, non-governmental organizations, and the public sector. Change does not stand up to reality without such an exercise in mapping reality, resources, problems, and opportunities.

It was a positively unattractive reality. While the technology sector has growth rates well above the growth in gross domestic product and the potential to create high value-added products, fewer and less well-trained people are choosing or could choose a career in the field. The number of students at technical universities has fallen by nearly half since the 1990s.

Each year, the number of graduates covers only half of the jobs available in the software industry. But it’s more than that: to use its potential in an increasingly technology-driven world, Romania needs people with the ability to create high value-added products. And this means that every technical university should allow its students, beyond an outstanding technical education, to experience and put into practice entrepreneurial thinking skills— product creation, business knowledge—things that enable them not only to be good programmers but above all to think and act in market terms.

It also means that we need to find a way to help children—especially those with few opportunities—break out of the trap of low grades, few achievements, and difficulty in gaining a good understanding of math and science.

It also means that we need to find a way to place strategic ‘bets’ on high-impact projects with the potential to multiply because resources are obviously limited.

If we could teach children and young people the love of solving essential problems and creating value-added solutions, we could change the reality we are starting from in a decade, maybe two.

****

SCHOOLS AND COMMUNITIES. LIDS WHO LOVE PROBLEMS

Intuitively, we might think that we choose a career when we choose a college, but our intuition would be wrong because, at that moment, we only get to choose from the options available to us, not from all the possible options. As we reach high school or college, a whole world of possibility has disappeared. In 2019, the TIMSS study (the international benchmark for assessing math and science skills in eighth grade) notes that 22% of Romanian students lack basic mathematical knowledge and skills, i.e., they cannot solve everyday problems using natural/integer numbers and simple geometric figures. For science, overall scores are even lower.

One of the direct consequences is that aspirations for technical careers, which require knowledge of mathematics, physics, or other sciences, vanish very early in children’s lives.

Fondul Științescu

“Often, the decision about ‘do I like or dislike math’ is actually made in fifth or sixth grade, when the transition is made from the concrete to the abstract, from simple math to more complicated concepts”, says Suzana Dobre, Director of Education Programs at RAF.

A set of options for potentially innovative, value-added, rewarding career fields becomes less feasible beginning in fifth grade, not at the end of high school.

Why is this happening? One of the critical reasons is how mathematics and science are taught, sliding too much towards abstraction and rote learning. This kind of teaching has consequences beyond the chasm between children and the hard sciences—it does not develop children’s ability to apply knowledge in real life and to understand and solve problems in the real world. A few years ago, an OECD paper noted the importance of creativity, innovation, and ingenuity in a knowledge-based world. It also acknowledged what cognitive science tells us: that a child retains knowledge better and can transfer knowledge to other areas more quickly when learning how to use it in real-life social and practical contexts.

Suppose we add to all this another reality of Romania, that of inequality. In that case, we have a slightly more complete picture: in 2018, the OECD measured the impact of socio-economic status on educational outcomes and found that, in Romania, almost 20% of the gaps in reading performance can be explained by the context in which children grow up, which is a lot. When children grow up in poverty, in isolated or complex social contexts, these circumstances rob them of a fifth of their chances.

“In rural areas, the number of children who don’t get a grade 5 in Math and can’t go to high school is increasing year after year”, says Camelia Crișan, CEO of the Progress Foundation, an organization that develops, together with RAF, programs for children in rural areas. In 2020, this percentage was 50%.

So, where do you begin to solve this problem?

One approach, a version of the theory of change, is that if you can get more kids to love science and acquire solid academic skills early on so that they can apply what they learn in real life, you can increase the number of people who choose careers in technology and innovation, people who can solve real problems and create high value-added products.

“We decided to work in two directions”, Suzana Dobre explains. “In schools, where children learn. And in communities”.

But the challenge of working in schools and building capacity in communities is far too broad. Therefore, you must make a strategic choice as to where you should use your limited resources to make the most significant impact.

As for schools, “if you look at international scores, our average is meager. We chose to go to schools in the middle, aiming to change how the average child learns and how the average teacher teaches”, explains Suzana.

And here, the question thus becomes how to contribute to creating a better system. Not how you change teachers one by one, but where and how you invest in creating a system that leads to change in the way teachers teach. And the way children learn.

WHY DOES THIS EGG FLOAT?

Eleven years ago, Fizica Altfel was RAF’s first program in the pre-university science education system. A learning endeavor, both for the RAF team and for the Centre for Educational Evaluation and Analysis (CEAE), the partner that developed it.

Physics Otherwise promotes inquiry-based learning, a method developed and tested over several decades. When children learn through inquiry, their attention is not directed toward memorizing information but solving concrete problems. Such as “Make an electric motor using just a battery, a magnet, and a wire”. Or “Put two similar eggs in liquid. Explain why one floats and one sinks?”

An obvious result of this method is that students understand and retain the electric current magnetic effect principles much better, or any other theoretical concept. But there are other consequences, at least as necessary for childhood and adult life, in a world that values practical intelligence: more curiosity about the world around us, the ability to think critically, to solve non-standard problems, to be creative, or to use knowledge in everyday life.

In 2011, 70 physics teachers entered a pilot program, where they learned and applied this new teaching method.

The inquiry-based learning theory was the basis of the new physics curriculum for secondary school and was then tested in 2012-2013 with remarkable results for children: performance improved by 18% .

The starting assumption was that curriculum reform would be an internally driven and supported process if the pilot program proved successful.

Fizica Altfel

Piloting any program involving the Foundation is of strategic importance to RAF: a relatively small investment can prove whether or not the initial assumptions of the theory of change are valid. In addition, “the condition for approval of the pilot program is, beyond having a theory of change aligned with the RAF strategy, that it contains a realistic answer to key questions about scaling up: who could take the program forward, what possible sources of funding exist”, Suzana explains. This is not to say that initial answers always hold up in real life, but that route between present reality and a desirable future is not possible without them.

In the case of Fizica Altfel, the initial investment was $200,000—when you consider that it’s about reforming the entire physics curriculum, 3,500 teachers, and a sustainable way to educate hundreds of thousands of children, it’s an investment with a potentially tremendous impact. The plan to scale it up nationally assumed that if the pilot program proved to be a success, the Ministry of Education would take it over, access European funds to train all the teachers, and build the expertise needed to take the method forward into the system. That didn’t happen. Although, in 2017, the Ministry approved the new physics curriculum for secondary school and introduced inquiry-based learning in both physics and chemistry, the program was only partially taken up by the Ministry.

Despite this, what started as a course has now turned into a community of practice: 2,600 physics teachers, more than half of the entire contingent, have taken these courses. The program has a platform, a methodological guide, evaluation tools, and an accreditation system. In 2021, Gabriela Deliu, one of the teachers in the program, observed that “the method of investigation has irreversibly penetrated Romanian schools. The good practice of what started as the initiative of just a small group tends to generalize to the whole Romanian educational system, and to me, this looks extraordinary”.

According to Cristian Hatu, president and founding member of CEAE, the community formed around the inquiry-based approach to teaching physics has a crucial role in supporting the program’s most challenging part. “The attitude change is the hardest. We support them to interact to share best practices, student experiences, and mistakes in a constructive environment in the community. It’s the most valuable thing that’s happened in the last five years”.

And speaking of leverage, this change, which has reached tens of thousands of children, was made possible with a total investment of nearly $1.5 million from RAF over ten years, or about €550 per teacher. Imagine what would be possible with more resources.

IT TAKES A VILLAGE TO EDUCATE A CHILD

We say it takes a village to raise a child, and this applies to education too; opportunities to learn science and love technology don’t begin and end at the school door. “Our goal is to have opportunities in as many communities as possible: science clubs, project fairs” says Suzana. In short, by 2026, RAF would like to see such opportunities in 1,000 of Romania’s 8,000 localities, especially in rural areas and smaller towns, mainly dedicated to families who don’t have access to existing programs.

One of the major barriers is related to the intervention model: especially in rural areas, it is costly to build a system that brings change to children. Or is it?

From 2009 to 2015, Camelia Crișan was part of the team that implemented the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation’s program to equip public libraries in Romania with computers and internet access. Nearly 2,300 libraries (out of 2,800 in Romania) and over 3,000 librarians were part of the program. “What if these libraries became centers where children in small towns and rural areas could learn to code and be introduced to technology in dedicated clubs? ” she wondered.

Since 2015, Camelia Crișan has been leading the Progress Foundation, a non-governmental organization that pilots local initiatives in education, inclusion, and community development, which she then scales up using public libraries as focal points for lifelong learning and centers for social innovation. In 2017, together with the RAF team, Progress created the pilot for a librarian-taught coding course in around 20 localities involving 700 children aged 10 to 14.

Code Kids

Code Kids is now in its third round of funding. It has evolved and transformed as RAF, Progress, and the Etic Association (the developer of the courses) have gained a better understanding of what works. Half of the project’s $1.2 million budget is funded by other partners. This is an element of sustainability, though, as Camelia says, “it’s been challenging because we’ve had to get out of the mindset of doing projects according to funders’ priorities and go out and convince them of our priorities”.

The original one-year course has turned into two years—a one-year module of practical coding for real problems has been added.

“That’s the most important thing”, says Camelia. “Children find problems in the world around them and solve them with code”. Once a year, in teams, they participate with their solutions in a national science and technology fair, Code Kids Fest.

What could you find at this fair? A sensor system that remotely turns the water tap in the greenhouse on and off, which was created by kids who had something better to do than make trips to the greenhouse. Or the clever hive of children in the village of Pietrari (Valcea), whose library has a coding club and 3D printers.

Code Kids is not yet at the stage where it has a crystallized model for scaling and long-term sustainability. Camelia still doesn’t know how she will be able to manage the project when its complexity increases when the number of clubs goes from 100 to 300. Together with RAF, she is analyzing and testing options. Change is never linear or according to plan.

AS IF YOU’RE TEACHING THE FUTURE TO CHILDREN

In 2012 and 2013, interesting things started to happen in the Romanian IT industry, such as large multinationals opening local offices, the development of a Romanian IT association, and the prospect for outstanding students to stay in the country and work in technology companies.

But, says Elena Coman, Program Director at Tech Soup Association, something was missing. Tech Soup has been working since 2013 on education programs for schools. In 2015, when it was becoming clear that the IT industry was becoming an opportunity for the economy and graduates, “the two worlds, education and industry, were not meeting”. In other words, schools were not anchored in this possible future. What we need to build, Elena and the Tech Soup team told themselves, is the ability to think in terms of the final product; product development “forces you out of the mindset of writing code and pushes you to learn other skills, like problem-solving, orientation towards meeting a customer need, collaboration, critical thinking”.

While working directly with students is very rewarding, it often feels like you’re always starting over with each generation. You can achieve a broader, more lasting impact over time by working with teachers. In 2016, Tech Soup and RAF tested a Bootcamp where 14 computer science teachers had an accelerated experience of learning and interacting with the industry. The possibility of a program that would motivate teachers to whet children’s appetites for applied knowledge emerged.

“I had no expectations. We took notes and wanted to see what the teachers did with these experiences afterward and if they replicated them in school”, Elena recalls.

Profesori de informatica în vizită la o companie de IT.

The Teaching the Future program has been developed over six years in the same manner a technology product is developed: by creating hypotheses, testing them, observing what happens, and deciding on the next steps. The essence of the program—to transfer product development skills to children through teachers—has not changed, but the way Teaching the Future supports teachers to do it is a process of continuous learning and adaptation: from the idea that you just need to connect with the industry to the revelation that you need to be giving teachers pedagogy skills, to the science behind product creation, to the values on which product development should be based. “Otherwise, totalitarian states are sometimes very good at technology”, says Elena.

Over the past two years, while the entire program moved exclusively online, Tech Soup understood one key thing about Teaching the Future: there is no “formula for success”.

“We thought”, Elena says, “that we would solve the problem if we found the right teaching methodology. But today, I know that there is more than one way to help teachers guide children in learning about product development. There are many ways, and we are now going with several initiatives in parallel”.

Essentially, the theory of change is the same: before they go to college, whichever college it may be, kids know how to create a product that incorporates technology. But the path to that has changed and evolved: today, Tech Soup aspires to create “the most important platform for ICT and computer science teachers, a learning and professional development space with the resources they need”.

For schools in small, single-industry towns, some teachers in the Teach the Future program have worked small miracles: community-funded product labs, prizes in national robotics competitions, and accelerators in high schools. There are about 2,000 teachers on the platform working or having worked with nearly 20,000 kids — a remarkable result with an investment of less than $100,000 annually.

The biggest obstacle to teaching children how to create products? “Short-term thinking in the education system in general”, Elena explains. “Teachers have no way to think about the future of the children they support because they are under pressure to think short-term, to focus on the next professional evaluation, the next merit grade. Nothing remarkable happens in a year”.

ALMOST ANYTHING WE CAN THINK OF

In December 2014, in a unique pilot project for Romania, four community foundations (Bucharest, Iași, Cluj, and Sibiu) said “yes” to RAF’s idea to create a community fundraising program to finance small community-based STEM education projects, Științescu. For most community foundations, Stiintescu was the first structured grantmaking exercise.

Today, 15 community foundations organize yearly community fundraising for the “Științescu Fund”. The projects are as diverse as the communities in which they occur. In Tecuci, a group of children learns how to design the city of the future; in Bucharest, children visit sewage treatment plants and learn about water; in Sâmpetru, children grow herbs.

RAF supports the “Științescu Fund” with matching funds of $10,000 annually in each community.

It might not seem like much, but the essence of Științescu is to plant seeds, to create a framework in which any initiative – whether it comes from a parent, a teacher, an engineer, an astronomer, a student, or a community lover – can be considered, tested and multiplied. “Parents get to work on projects alongside their children. Children discover science in a hands-on, experiential, sensory way by working together on projects. Some are rethinking their options and discovering passions that can change their future”, says Ruxandra Sasu, Senior Program Officer at RAF.

Community foundations have so far funded almost 500 projects, benefiting 64,000 children. They have brought together from communities 4,000 people who have donated to local funds and nearly 450 companies. More than $1.3 million has funded these “seed” applied science projects.

Teoria schimbarii în programele de tehnologie si inovație

****

UNIVERSITIES. The path from code to product

When we refer to “education adapted to the needs of the labor market”, what are we really talking about? We could understand that we want better workers. It’s important, but nowhere near as valuable a stake as this: innovative thinking and understanding the market and the product are key to successful careers, added value, and prosperity.

In 2021, Romania ranked 48th in the Global Innovation Index out of 132 countries globally. It’s a position that hasn’t changed much in 10 years. Among European countries, it ranks 31st out of 39. One of the big weaknesses, according to IGI scores, is the impeded collaboration between universities and industry. Another is the number of universities at the top of the rankings. Another is the relatively small number of people employed in jobs requiring sophisticated knowledge. By contrast, the number of new companies per thousand inhabitants puts us in a respectable 21st place even though there are far fewer technology-intensive companies than the EU average, according to the Digital Society and Economy Index (DESI 2021).

Roxana Vitan felicitând câștigătorii Innovation Labs Green Prize 2021

With strategic investment linked to entrepreneurial education in technical university centers, where technology is already taught, Romania would have more capacity to identify needs and solve problems through high value-added products. This theory of change, in a nutshell, is the basis of RAF strategy in university education, and, simply put, it brings the market into the school and connects the school with innovation that brings concrete value in the real world.

It’s a long and complicated road. It started in 2015 when RAF brought industry, experts, and academia around the table to understand the problems and what could be done. It has continued with initiatives that have succeeded and scaled nationally, like Innovation Labs, and initiatives that haven’t made it beyond the pilot project phase but have been seeds of learning for programs aimed at systemic change and repositioning universities in the ecosystem, like Fulbright-RAF grants.

Paul Baran runs RAF programs in universities and, after nearly seven years of experience, knows that this kind of change is a long-term endeavor.

“We’re at a time when we’re seeing real change. In 15, maybe 20 years, we can look at major changes. The aspiration of the programs is the same, but the way they work is transforming as we move forward”.

****

WE DON’T EVEN KNOW HOW FAR WE COULD GO

If you want to change something, you must start by understanding where you are in the first place. Someone has to provide a benchmark that creates an aspiration: “You are here; you could go so much farther if you do these things”.

Universities in Romania had the opportunity to explore, for the first time, how innovative and entrepreneurial they are and what capacity and potential they have that would help them become even better. The assessment tool, which has created new aspirations, is HEInnovate, a methodology for universities developed by the OECD and the European Commission.

In the Entrepreneurial University program, developed by RAF together with Junior Achievement Romania (an organization with a lot of experience in introducing entrepreneurship programs in educational institutions), more than 26 university centers from all over Romania brought together professors, students, experts, academic and faculty management who together went through the exercise of assessing impact, organizational capacity, digital and education skills, as well as support for entrepreneurship.

“For the first time, this program has brought together universities, the business community, and the academic community to have an honest discussion about where each educational institution stands”, says Paul.

Access to a strategic tool for assessing how a faculty is organized and operates to encourage entrepreneurship and innovation has effects beyond the assessment itself. For example, Ovidius University of Constanta announced in January 2021 the creation of an innovation center to act as a hub for collaboration between companies and academia.

****

BRIDGES FOR IDEAS TO TRAVEL BETWEEN WORLDS

To create change, apart from understanding where you are, you need a model to aspire to, a desirable reality to want to build. And to create sustainable change, the kind that happens from within, you need the will, faith, motivation, and enthusiasm of the people part of the system.

The Ain Center for Entrepreneurship at the University of Rochester in the United States is a possible benchmark of what an entrepreneurship and innovation center at an academic institution could look like. It is a multidisciplinary center connected to the business environment, with an extensive network of experts, mentors, and support systems. It aims to turn ideas into companies that create value in all areas of society: from art to education, from business to healthcare.

Since 2016, the Fulbright-RAF Scholar Award program has awarded one academic semester scholarship for a customized program at the Ain Center for Entrepreneurship for more than 30 professors from technical universities in Romania. They are the ones who will be inspired and will then have the tools and knowledge to create, in the universities where they teach, the seeds of future entrepreneurial hubs. In addition, a network of alumni formed in the Association for Entrepreneurship Education can also support communication and joint or individual teacher initiatives.

“One of the most important decisions”, says Paul, “was to invite the heads of the respective universities to visit the Ain Center for Entrepreneurship. When we designed the program, we didn’t think how important this component would be in opening up new perspectives and aspirations in universities”.

Suppose today we find soft skills, design thinking, interdisciplinary collaboration, and cross-faculty — or even cross-university — courses in technical faculties. In that case, it is probably to a large extent due to the scholarship program.

Lidia Alexa is a lecturer at the Gheorghe Asachi Technical University in Iasi. She is one of the professors in the 2018 Fulbright-RAF grant class and one of the 32 grantees. She describes the experience as follows: “It really took me out of my comfort zone and made me discover new things about myself. I understood what an entrepreneurial system means and what role a university can play as a creator of context and opportunity”. Two years ago, she took over the coordination of a cross-university project to introduce third-year entrepreneurship education courses in all faculties.” What’s happening here is major because, as far as I know, there is no such cross-faculty course in any university in Romania”, Lidia explains. It’s the first year of teaching the course, but the results are interesting; although it’s optional, it’s very well attended. “And I treat it like a minimum viable product (MVP) — I’m testing what I’ve learned about creating a good product”, Lidia says.

She continues to collaborate with the University of Rochester as an evaluator in their business competitions or as a mentor for teams. If she were to describe what she’s learned about how to create an entrepreneurship course, she’d say that “if, when designing the course, you focus it on student needs and empathy, almost anything can work. As a teacher, you’re tempted to go into the course from a know-it-all position. Here, I’m more of a process moderator”.

Paul Baran, Prorectorul UPB Valentin Navrapescu, Profesorul Universitar Elena Ovreiu și Roxana Vitan în vizită de lucru la University of Rochester

Elena Ovreiu is also a Fulbright-RAF Fellow and the driving force behind another trans-disciplinary initiative of a different nature. Elena teaches eHealth, Biodesign, and Medical Device Software at the Bucharest Polytechnical University. She is preparing to launch BIOdyssey in the fall of 2022: a joint project for students from the Polytechnical Uni and the Faculty of Medicine consisting of an accelerator for innovation in healthcare with an integrated entrepreneurship course. Created in partnership with Israel’s Technion University, the project brings together multidisciplinary teams to solve real problems in Romanian hospitals. Beyond the Technion’s expertise, Elena wants to bring to BIOdyssey the expertise of investors from venture funds and accelerators she met during her fellowship in the United States.

“Building bridges is essential”, says Elena. “There is knowledge about how we can do innovation and improve hospitals. We need to find shortcuts, using existing methods and models and adapting them here”.

A bridge, but of an entirely different nature, is the one that is built between ideas and the structures created to support them. The Association for Entrepreneurship Education is such a hub. Early Fulbright-RAF grantees created it to hold together and support alumni and other teachers building entrepreneurship programs. Today, it is led by Razvan Crăciunescu. An alumnus himself and a lecturer at the Polytechnical Uni, he is the creator of Romania’s first lab for Innovation in Entrepreneurship and Future Technologies. “The lab is a result of the scholarship; we organize summer classes to try to educate students in entrepreneurship,” Răzvan says.

There is also another strategic function of the Association: with funding from RAF, it can award small grants to professors who have graduated from the scholarships to implement different ideas for courses, workshops, or experiences for students, provided they are based on entrepreneurship education. Or, it can partially fund initiatives such as BIOdyssey.

*****

THIS VAST LABORATORY OF IDEAS

Once a year, in five major university centers in Romania, students have the opportunity to take their ideas “out into the world” in the country’s largest technology startup accelerator — Innovation Labs. Hundreds of multidisciplinary teams from 16 university centers sign up in Bucharest, Sibiu, Iasi, Cluj, and Timisoara to work with nearly 200 mentors and entrepreneurs on ideas that become products and companies that create value.

Innovation Labs started ten years ago at the Polytechnical University in Bucharest, following a conversation between two former university colleagues. Răzvan Rughiniș, today a professor, and Andrei Pitiș, one of the outstanding technological entrepreneurs, started with the question, “how do you get students to aspire to more than just becoming employees of a large, multinational technology company?”

Innovation Labs: Răzvan Rughiniș și Andrei Pițiș

In 2015, RAF put a challenge on the table — how can Innovation Labs be scaled up, and how can it be replicated in other centers? With this question, an operating principle of all RAF programs, that they must prove their ability to scale, met with the ambition and expertise of a project ready for the next level; Innovation Labs expanded to Cluj, Sibiu, and Timisoara. The following year, it reached Iasi. The program is much more than an accelerator. It builds what Răzvan calls “another horizon of imagination”. It puts the possibility of an entrepreneurial path among valid career options. “We”, says Razvan, “put the concept of a good-paying job and the opportunity to create impact through entrepreneurship in the same conversation about what a successful career is”.

Collaboration between university centers is another guiding principle for RAF projects in universities. And the growth of Innovation Labs is, in part, due to this principle. “After the first year or two of Fulbright-RAF grants, I started organizing alumni meetings. I encouraged them to get involved in Innovation Labs. In fact, they were also the basis for expanding to other university centers”. Also, from communication and collaboration between professors came what Paul calls “a major change” in Innovation Labs: organizing competitions on areas of interest such as agritech, medtech, security, which brings students from very different majors together in multidisciplinary teams.

This ‘cross-pollination,’ which takes place over time, requires trust, patience, and measurements other than strictly numerical ones; this is the real stake of innovation and real-world problem-solving.

****

This whole development is a learning process for RAF, its partners, and the program beneficiaries. It is an exercise to project into the future and build a different reality by going backward from that desirable future. Small, experimental, strategically placed grants bring ideas that take programs forward to life. If successful, they can be scaled up and scaled out. If unsuccessful, they can be transformed or seen as the price of learning. Because this is uncharted territory, for which no one has the perfect solution, the key is to have a coalition of partners who see and understand the reality and aspirations in the same way.

RAF’s role in this architecture of change is not just to take the risk of putting the seed venture capital on the table. It is also to provide the comfort that the RAF will be there for the long term once a direction is chosen. But, perhaps most importantly, it is to create and facilitate a conversation.

“We don’t hold solutions”, says Roxana Vitan, president of RAF. “We help everyone else find those solutions that are suitable. They may not be the best ones, but they are certainly the right ones because that is the way forward”.

It’s a consultative, entrepreneurial process that differs from other funders. Measurable results — in numbers of beneficiaries, in financial figures — are important. But the ones that tell you about impact are often much less measurable but much more relevant: children coming back to mentor other children, teachers starting new initiatives, a change of mindset in a community, an entrepreneur changing people’s lives. The impact is often what happens in five or ten years when people almost forget who initiated the change. But aspiring to change who creates value in an economy and how this value comes to life, being a facilitator and a witness to change is a more exciting stake than aspiring to take credit for that change.